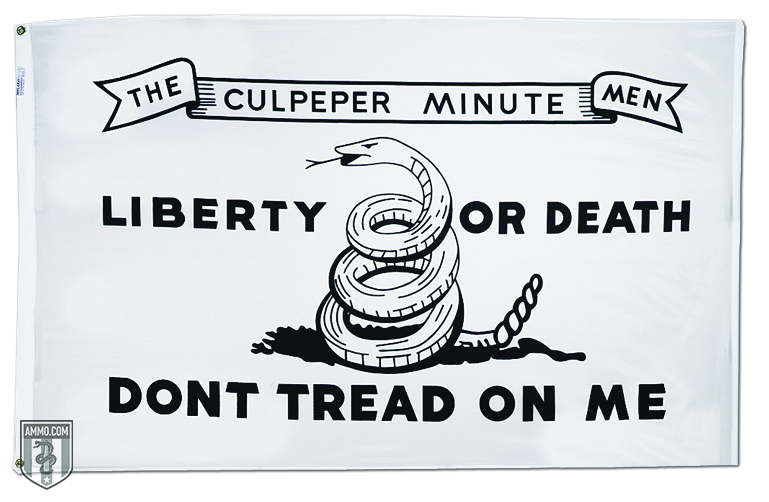

The Culpeper Flag is often mistaken as a modern variation of the iconic “Don’t Tread On Me” Gadsden Flag – and rightly so. What many don’t know is that the Culpeper Flag was inspired by its Gadsden counterpart, and both have become touchstones of the Second Amendment Movement.

While remarkably similar to its Gadsden relative, the flag of the Culpeper Minutemen is arguably cooler – and significantly more obscure. While it has the same coiled rattlesnake and “Don’t Tread on Me” legend, the Culpeper Flag is white, it carries the additional motto “Liberty or Death,” and when historically correct, a banner bearing the name of the Culpeper Minutemen.

The rattlesnake had been a symbol of American patriotism since the time of the French and Indians Wars. In 1751, Benjamin Franklin wrote an editorial satirically proposing that, in return for boatloads of convicts being shipped to the American Colonies, that the Colonies should return the favor by shipping back a boat filled with rattlesnakes to be dispersed. Three years later in 1754, Franklin published his famous “Join or Die” comic. This early symbol of American unity urged colonists in Albany to join the collective defense of the American Colonies during the French and Indian Wars. The rattlesnake symbol and the “join or die” slogan once again became a popular mascot of American unity.

The Origins of the Culpeper Militia

The Culpeper Minutemen were formed on July 17, 1775, in a district created by the Third Virginia Convention. This district consisted of the Orange, Fauquier and the titular Culpeper counties. In September of that year, 200 men were recruited for four companies of 50 men from Culpeper and Fauquier, with an additional 100 men for two companies from Orange. By order of the District Committee of Safety, the Culpeper Minutemen met under a large oak tree in a large field currently part of Yowell Meadow Park in Culpeper, Virginia.

When the Revolutionary War came, the Culpeper Minutemen chose the Patriot side. It was at this time that they also adopted their standard bearer that can be seen adorning pickup trucks of modern-day patriots from sea to shining sea. Their first action during the American Revolution was to defend Virginia capital Williamsburg after the Royal Governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, confiscated the gunpowder.

The Culpeper Boys Arrive in Williamsburg

They cut quite a sight arriving in the aristocratic capital, wearing heavy linen shirts dyed the color of the local foliage and carrying tomahawks and knives for scalping. Philip Slaughter, who served with the Culpeper boys as a 16 year old, said that the colonists looked at them much as they might the Indians themselves. The Culpeper Minutemen, however, were no roughnecks, but a disciplined and orderly squad who quickly earned the respect of their new charges.

During the Revolutionary War, the area where the Culpeper boys were organized was still the frontier. So they were often called to more populated and settled areas. For example, the Culpeper Minutemen fought in Hampton when the British tried to land troops there, at the request of the local authorities. The Culpeper Militia successfully mounted an attack on the arriving ships, shooting the men who were manning the cannons and guns on the ship, preventing the British from landing.

The Battle of Great Bridge

The Culpeper Minutemen were also involved in the December 1775 Battle of Great Bridge, which is one of the places where historians agree that their flag was carried in battle. Here they met the troops of their old enemy Dunmore. This was an American rout. It marked the final gasp of colonial power in Virginia.

While it doesn’t get as much attention in history books, the situation in Revolutionary Virginia was arguably as tense as it was in Revolutionary Massachusetts. Dunmore had dismissed the colonial assembly, the House of Burgesses, as well as the aforementioned confiscation of gunpowder. The gunpowder was confiscated without incident, but Dunmore feared for his life and fled the colonial capital, placing his family on a Royal Navy ship in the harbor.

In October, Dunmore had finally gained enough military support among Loyalists in the colony to begin military operations. This included attacks on the local civilian populations in an attempt to confiscate military materials that might be used by the rebels. On November 7, Dunmore declared martial law and even went so far as to offer emancipation to all slaves willing to fight in the British Army. Indeed, he was able to raise an entire regiment to that effect.

The local forces numbered a scant 400. However, reinforcements from neighboring areas, including the Culpeper boys, helped to balloon this number. Dunmore, however, had old intelligence that left the numbers at the original 400. The battle ended with the British forces spiking their guns to avoid capture by the Revolutionary forces.

When all was said and done, there were 62 British casualties by British count and 102 by the count of the rebels. The rebels had only a single casualty – a slight thumb wound. The Virginians considered this to be their Bunker Hill. The Patriots refused to allow the overcrowded ships (where the Tories sought refuge) to be resupplied, which resulted in the bombardment of Norfolk and its looting and destruction by rebels. Dunmore, considered the greatest threat to the Revolution by many senior rebel officers, was eventually forced out of Virginia entirely in August 1776.

Reports indicated that the British were highly intimidated by the reputation of the frontiersmen who would be arriving at the battle. This undoubtedly provided them with a psychological advantage in what was an important battle.

The Death and Resurrection of the Culpeper Minutemen

The Committee of Safety ordered the group to disband in January 1776, however, almost all of the Culpeper boys kept on fighting – either as Continental militiamen or underneath senior officers such as Daniel Morgan.

The fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, John Marshall, was one of the first Culpeper boys.

When the War Between the States came, the Culpeper Minutemen were reconstituted under the old oak tree where they first organized generations prior. This was in 1860, and they once again carried the same flag as their forefathers. They were eventually integrated into the regular army of the Confederate States of America, as part of Company B of the 13th Virginia Infantry, where they served for the duration of the Civil War.

The Minutemen came together again during the Spanish-American War, but were never activated. During World War I, the Culpeper boys organized once again, this time under the auspices of the 116th Infantry. The modern-day Alpha Company Detachment, 2nd Regiment of the Virginia Defense Force, considers themselves to be a descendent of the Culpeper Minutemen, probably with their roots in the First World War.

While many of the Revolutionary War flags flown by Patriots today have dubious origins, the Culpeper Flag is one of the few banners that we know for certain was flown by Patriots during the Revolutionary period. It also offers a succinct statement of the values of the American nation: Liberty or Death – and a stern warning to those who would threaten our liberty.

The Culpeper Minutemen Flag: The History of the Banner Flown by a Militia of Patriots originally appeared in The Resistance Library at Ammo.com.

Site Information

About Us

- RonPaulForums.com is an independent grassroots outfit not officially connected to Ron Paul but dedicated to his mission. For more information see our Mission Statement.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Connect With Us