In what may be the largest worker strike in history, last week India came to a halt for two days when at least 200 million workers - about 16% of India's 1.25 billion population - in the country's public, services, communications and agriculture sectors staged a strike across the country organized by ten labor unions against what they called the anti-national and anti-worker policies of the BJP-led government, and against a new labor law that would undermine the rights of workers and unions.

The strike is a protest against new legislation that passed on 2 January, and is a de facto verdict on Prime Minister Narendra Modi providing an opportunity for millions of workers to protest against high prices and high levels of unemployment, something we touched upon in "The Indian Railway System Announced 63,000 Job Openings... 19 Million People Applied."

John Dayal, general secretary of the All India Christian Council, told AsiaNews that the event was exceptional, "one of the largest ever organised in the country, planned in advance in every detail." In his view, the most important thing is that it "is taking place on the eve of general elections that will mark the fate of the prime minister".

While the massive strike took place in an overall context of calm, there were numerous incidents confirming that social anger in the world's second most populous nation is also approaching a breaking point: protesters blocked several cities, clashes broke out and damage were reported; a 57-year-old woman died in in Mundagod, a city in northern Karnataka, during a local protest. In Maharashtra more than 5,000 workers blocked the Mumbai-Baroda-Jaipur-Delhi highway. In Puducherry (Pondicherry), on the east coast, protesters hurled stones at a Tamil Nadu state bus. Transport services closed and rail services were disrupted in Kerala. In Odisha (Orissa), shops, schools, offices and markets shut down for 48 hours. In West Bengal, protesters burnt effigies of Prime Minister Modi.

The national strike was an initiative of the Central Trade Unions (CTU), which is an India-wide labor federation. Unions are opposed to the Trade Unions (Amendment) Bill of 2018 which modified the Trade Union Act of 1926.

Under the law, trade union recognition is mandatory at both at national and state level. However, workers believe that the new law grants the government discretionary power in recognizing labor organizations, effectively eliminating the current bargaining process involving employees, employers and the government.

Unions demanded the enactment of the Social Security Act to protect workers and a minimum wage of 24,000 rupees (more than US$ 340) for the unorganised transport sector.

Workers in banking, insurance, healthcare, education, transport, electricity and coal mining also joined the strike. Student groups also protested as did farmersí associations that have threatened to call a gramin hartal, a rural strike. Farmers have been protesting for months over the harsh conditions in the countryside, burdened by debt and an wave of suicides.

Addressing the media after the 2-day strike, Amarjeet Kaur of AITUC said around eight states witnessed a complete shutdown, largely in the northeast, Kerala, Bihar and Goa. There were over 20 crore workers who had joined the strike.

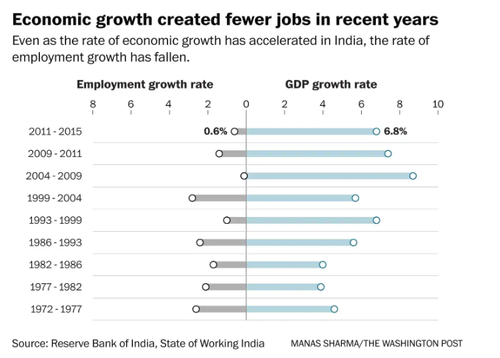

The massive strike comes at an critical inflection point for India, which is one of the world's fastest growing economies, yet isnít generating enough jobs for its educated young populace.

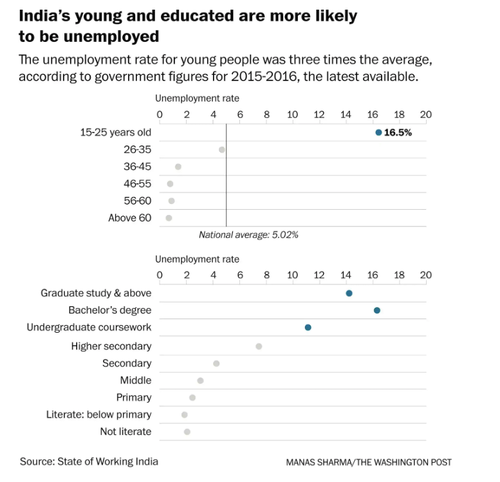

A recent Washington Post article estimated that the number of people in India between age of 15 and 34 is expected to hit 480 million by the year 2021. They have higher literacy levels and are staying in school longer than any other previous generation. The surge of youths could be an immense opportunity for the country, if it can find a way to put them to work. But the employment trends in the country remain gloomy.

An analysis performed by Azim Premji University shows that unemployment between 2011 and 2016 in nearly all Indian states was rising. The jobless rates for younger people and those with higher education also increased sharply. For instance, for college graduates, it grew from 4.1% to 8.4%.

Ajit Ghose, an economist at the Institute for Human Development in Delhi, said that the country needs to generate jobs not just for the 6 million to 8 million new workforce entrants annually, but also for people like women who are working less than they would be if they could get jobs at a decent wage. The same economist notes that India has about 104 million "surplus" workers.

Expanding the labor market that much is a tall task for any government, not just India. Modi's track record of job creation also remains somewhat of a mystery, as the country hasnít offered nationwide employment data since 2016. The ministries of labor and statistics have conducted surveys of Indian households, but the results have not been made public.

Amit Basole, an economist at Azim Premji University, said: ďItís anybodyís guess whether weíll see any employment statistics come out before the 2019 elections.Ē

More at: https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-...s-took-streets

Site Information

About Us

- RonPaulForums.com is an independent grassroots outfit not officially connected to Ron Paul but dedicated to his mission. For more information see our Mission Statement.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Connect With Us