Africa::

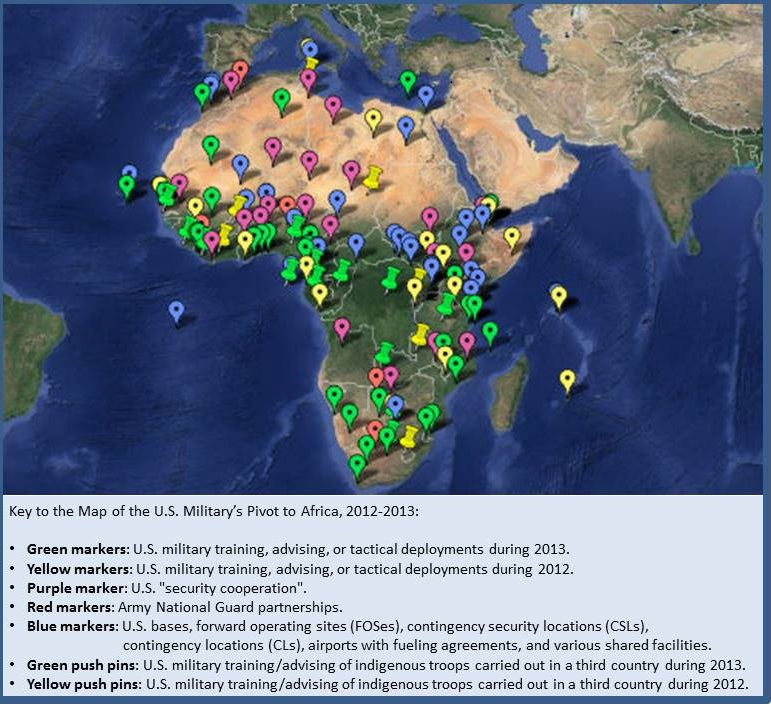

[Because of prior colonialism], I think that if African people knew the extent to which the United States operated there, it might cause real problems. Africa Command claims they only have one base on the continent of Africa, Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti; however:

- Within a 10-mile radius of Camp Lemonnier, there’s actually another base, Chabelley Airfield, where they run all drone operations out of. So, it’s not even true for that one [small] country. There’s takeoffs or landings of at least 16 drones per day from Djibouti right now, perhaps more.

A lot of these are surveillance drones, but the ones that are armed are generally conducting the war in Yemen and also in Somalia.

- I don’t want to steal all my thunder from the forthcoming piece at TomDispatch; it’ll be out at TomDispatch this week, but I can tell you that there are scores of bases on the continent. It’s upwards of 50 U.S. outposts, bases, access sites, spread all across Africa.

- The U.S. military is now involved in more than 90 percent of Africa’s 54 nations [so greater than 48 countries in Africa alone].

- AFRICOM carried out 674 missions across the African continent last year—an average of nearly two a day, and a 300 percent jump from previous years. These are anything from night raids that have been launched recently in Libya and Somalia.

- There’s a shadow war that’s going on in Somalia. And we also see it elsewhere.

- There are now 11 of what they call contingency security locations, CSLs, spread across the continent. These are basically very austere bases that can be ramped up in very—very quickly. The U.S. maintains rapid response forces in Spain and in Italy. And these forces are designed to deploy to these 11 CSLs across the continent so that the U.S. can respond in the event of another Benghazi-type crisis.

- I worked on a series at The Intercept called "The Drone Papers," where we outline the proliferation of drone bases now that dot the African continent. [In addition to the two bases in Djibouti, here are some examples]:

- There’s just been an announcement of a new drone base being set up in Cameroon to go after militants from Boko Haram, because that force is also spreading across the continent.

- There’s also two drone bases that are supposedly set up in Somalia now.

- Drone bases are also in:

- Chad;

- Ethiopia;

- Niger:

- They’re flying out of the capital, Niamey.

- And they’re in the process right now of setting up a new drone base at Agadez.

If you travel anywhere on the African continent, you’ll see that the Chinese have moved in, in a very big way, over the last decade. They’ve pursued a campaign of economic engagement across the continent, and very, very public projects. Everywhere you go, they’re building an airport, they’re building roads, they’re putting up government facilities—tangible projects that Africans can see. This is the strategy they’ve pursued to gain influence in Africa. The U.S. has gone a different route. They’ve pursued an antiterror whack-a-mole strategy, where they send small teams around the continent, they send drones. They try to tamp down terror groups and seem to only spread them around. They’ve also pumped in tremendous amounts of money, but this is to bolster African militaries with rather dubious human rights records.

There’s a U.S. expansion all across the continent, east to west. If you look at the effects on the ground on the continent, it’s been rather dismaying these last years. If you look at the groups that we’re training on the continent, the militaries we’re training, and then you compare them to the State Department’s own list of militaries that are carrying out human rights abuses, that are acting in undemocratic ways, you see that these are the same forces. The U.S. is linked up with forces that are generally seen as repressive, even by our own government. [

Here are some examples]:

- [Libya]: Libya is a great example --The U.S. joined a coalition war to oust dictator Muammar Gaddafi. And I think that it was seen as a great success. Gaddafi fell, and it seemed like U.S. policies had played out just as they were drawn up in Washington. Instead, though, we saw that Libya has descended into chaos, and it’s been a nightmare for the Libyan people ever since—a complete catastrophe.

- [Mali]: [Libya's problems] had a tendency to spread across the continent. Gaddafi had Tuaregs from Mali who worked for him. They were elite troops. As his regime was falling, the Tuaregs raided his weapons stores, and they moved into Mali, into their traditional homeland, to carve out their own nation there. When they did that, the U.S.-backed military in Mali, that we had been training for years, began to disintegrate. That’s when the U.S.-trained officer decided that he could do a better job, and he overthrew the democratically elected government of Mali 2 years ago. But he proved no better at fighting the Tuaregs than the government he overthrew. As a result, Islamist rebels came in and pushed out his forces and the Tuaregs, and were making great gains in the country, looked poised to take it over. The U.S. decided to intervene again, another military intervention. We backed the French and an African force to go in and stop the Islamists. We were able to, with these proxies—which is the preferred method of warfare on the African continent—arrest the Islamists’ advance, but now Mali has descended into a low-level insurgency. And it’s been like this for several years now.

- [Burkina Faso]: Last year, a U.S.-trained officer overthrew the government of Burkina Faso.

- [Boko Haram and Egypt and across the continent]: The weapons that the Tuaregs originally had were taken by the Islamists and have now spread across the continent. You can find those weapons in the hands of Boko Haram now, even as far away as Sinai in Egypt.

- [Kenya]: Kenyan forces that we’ve been backing have set up extensive smuggling networks in Somalia. They seem to have been putting down roots themselves in bases. In Kismayo, where the U.S. is supposedly flying drones out of and has a special operations base. That’s now apparently a smuggling hub for the Kenyan military, in league with the terrorist group al-Shabab. They seem to be working in concert to smuggle sugar. There’s also been charcoal smuggling in the region. So—and this is a force that the U.S. has been backing and funding. They’ve put a lot of money into training Kenyan forces to act as a proxy in Somalia. But they haven’t been very successful in tamping down violence. Actually, it’s spread the violence into Kenya now. And the Kenyans have been seen by many groups as being exceptionally corrupt, conducting smuggling around the region, and also they’ve committed human rights abuses.

- [Chad]: Chad, we’ve pumped a lot of money into using the Chadians as proxy forces. We backed Chad to go into the Central African Republic, and they committed a massacre there; they machine-gunned a marketplace filled with civilians.

- [South Sudan]: South Sudan. This was a nation-building project for the United States, its one nation-building effort in Africa. The Obama administration—followed up on the Bush administration in pushing this breakaway portion of Sudan to become its own independent country, and put a lot of money, time and effort into South Sudan. And then it exploded into civil war in 2013. This was supposed to be a great American success story, something the Obama administration had pushed as a model for what the United States can do. Now, I think the U.S. has really lost out to China there, in many ways. Somehow, the Chinese have enabled, through the U.N., an infantry battalion of their own to be put into South Sudan to guard the oil fields there. The Chinese have great oil interests in South Sudan. And the United States, because it pays for U.N. troops, peacekeepers around the world, is in effect paying Chinese troops to guard Chinese oil interests in South Sudan.

I happened to be in a camp, a U.N. camp for internally displaced people in South Sudan. And, you know, I came across a young boy there who was wearing a Barack Obama T-shirt, and it said "Obama, my dream." And I asked him about his dream. And at one time he had dreams of maybe being a president, like Barack Obama, about getting a good education. Now he was stranded at a U.N. base, unable to go back home because the military that we had funded and trained in South Sudan had attacked his people, had killed his uncle, had driven tens of thousands of people in South Sudan into what at the time and even today are, in effect, open-air prisons. People are too afraid to go back home. And this is because of the government that we supported for years.

It’s ironic because when a senior Pentagon official was asked after 9/11 about the presence of transnational terror groups on the continent,

he wasn’t able to come up with any. The best he could come up with was that militants in Somalia had saluted Osama bin Laden. That was the extent of it. They hadn’t actually attacked anywhere outside of Somalia. They had local grievances, and they were contained. But the U.S. got into its head that Africa was a place that could be a heartland for terrorism, so it pumped in a tremendous amount of money, sent in forces, conducted all these training operations, set up small bases around the continent—all of it to shore up the continent against terror. Instead, you look anywhere on the continent today, and you see a proliferation of terror groups—ISIS, Boko Haram, al-Shabab, al-Mourabitoun, Ansaru, over and over. The Pentagon won’t name all the groups that it sees as threats, but it’s somewhere

around 50 that it claims are groups on the continent that are opposed to U.S. interests.

U.S. Africa Command admits very little. That was the reason why I wrote this book. I wasn’t intending on spending years covering the U.S. in Africa. Basically, I noticed that there were some things going on that told me there was an expansion underway. I saw that the U.S. was putting in a logistics network in Africa a few years ago. And I knew that there’s only one reason for this. You don’t create a network of sea and land routes to transport goods, unless you plan on building bases and putting people there. But when I asked Africa Command what was going on, all they told me was about a very light footprint, almost nothing was happening. And I knew it wasn’t the case. You know, if they had told me anything resembling reality, I think I would have written one piece and moved on. But I knew they were trying to spin me, I knew they weren’t being upfront and honest, so I decided to dig into it. And what I found is something far beyond anything you would find on AFRICOM’s website. They talk about a few humanitarian projects, building schools, donating shoes to orphans, this type of thing. But really, we’re seeing a massive expansion in the form of bases, drone warfare, special ops.

[As far as the humanitarian projects,] I got a hold of a classified report that was done by an inspector general, taking a look at these humanitarian projects, the only things that Africa Command will really talk about. They say that they’re great successes. The inspector general said otherwise. They looked around and saw projects where the U.S. hadn’t done follow-ups. They hadn’t checked with the community beforehand to see what people needed. For example they built water well projects that weren’t suited to the community. People didn’t know how to maintain them in any way. They weren’t given any guidance. And within a couple years, these were crumbling. And that quote there, "monuments to failure," was one of—a U.S. official on the continent saying that he was very afraid that all these projects would, within a couple years, become failures, and they would stand as monuments to U.S. failure on the continent.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Connect With Us